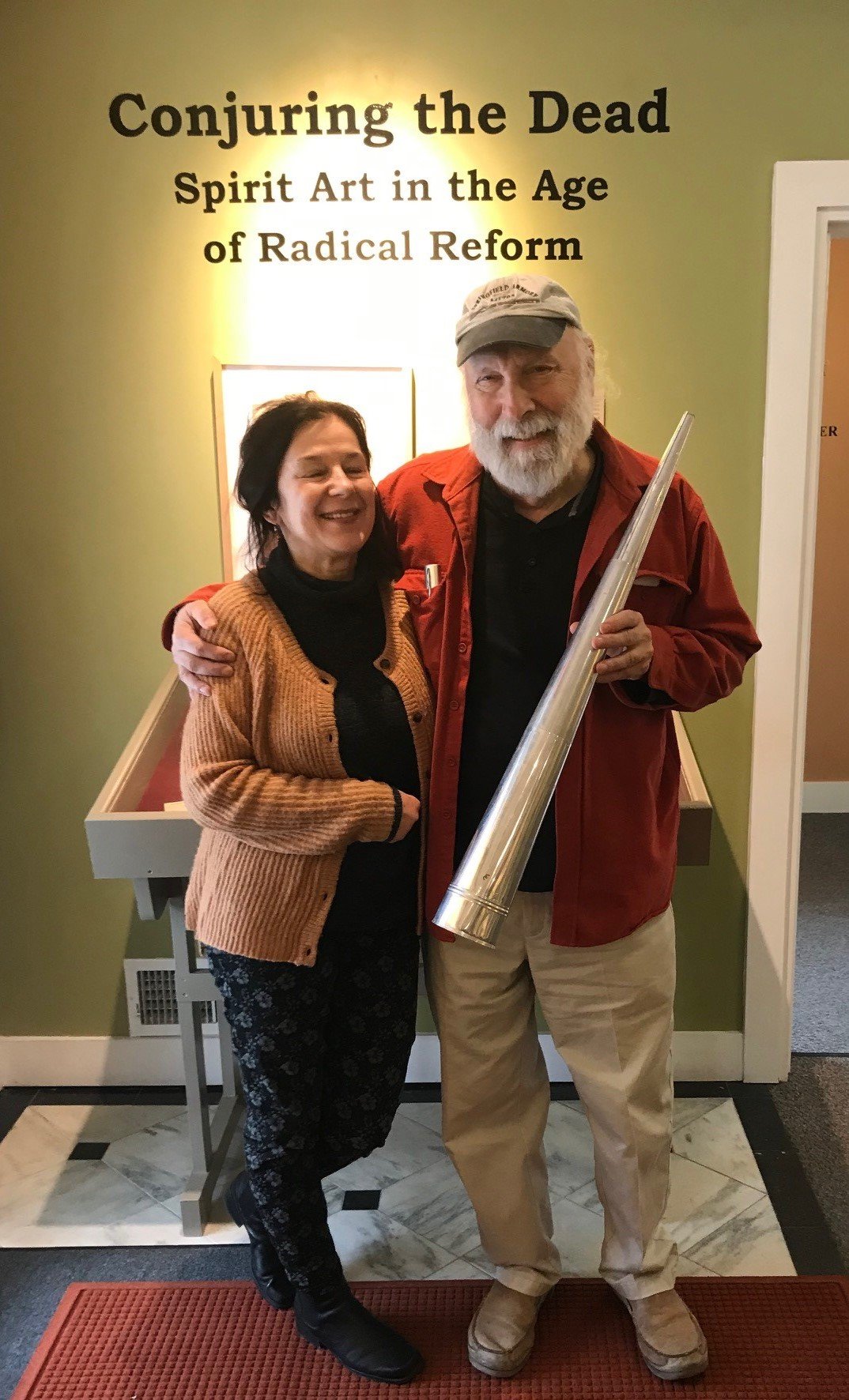

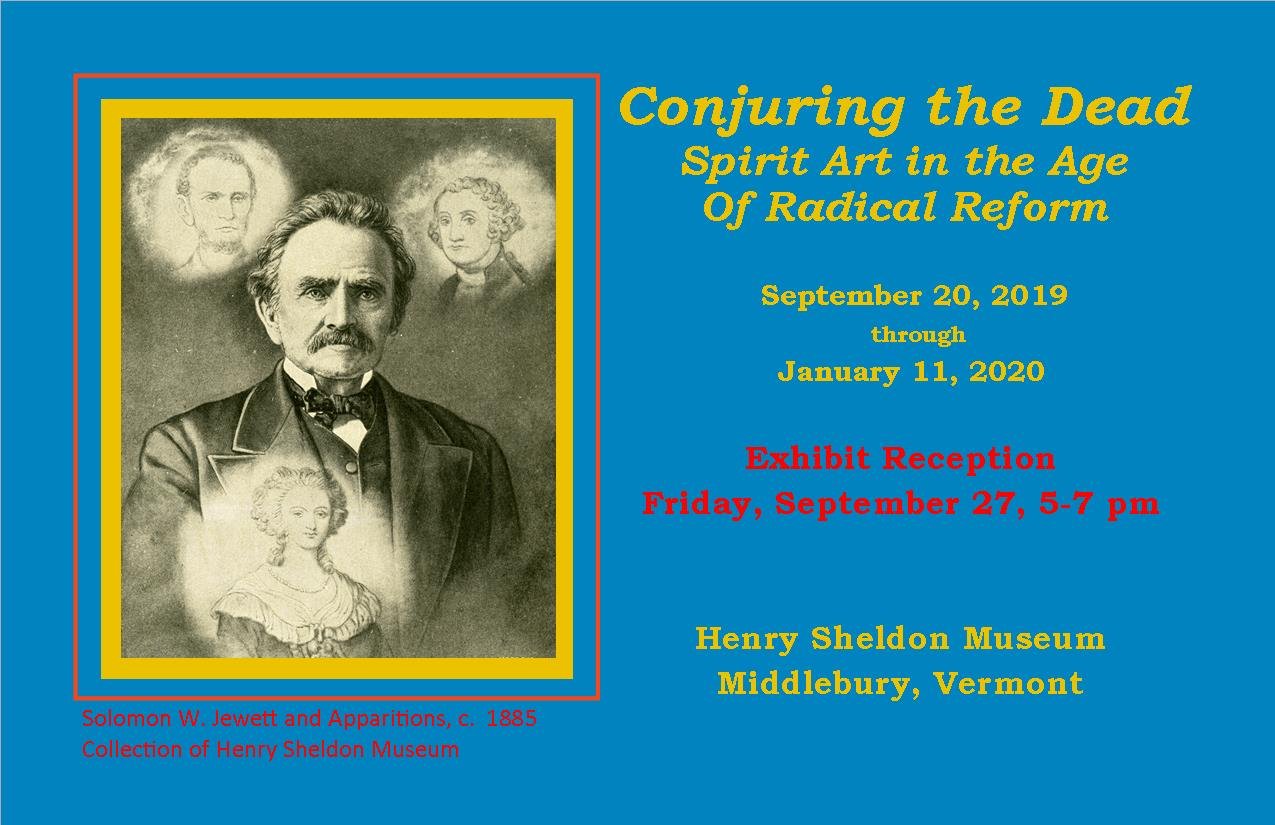

Conjuring The Dead: Spirit Art In The Age Of Radical Reform

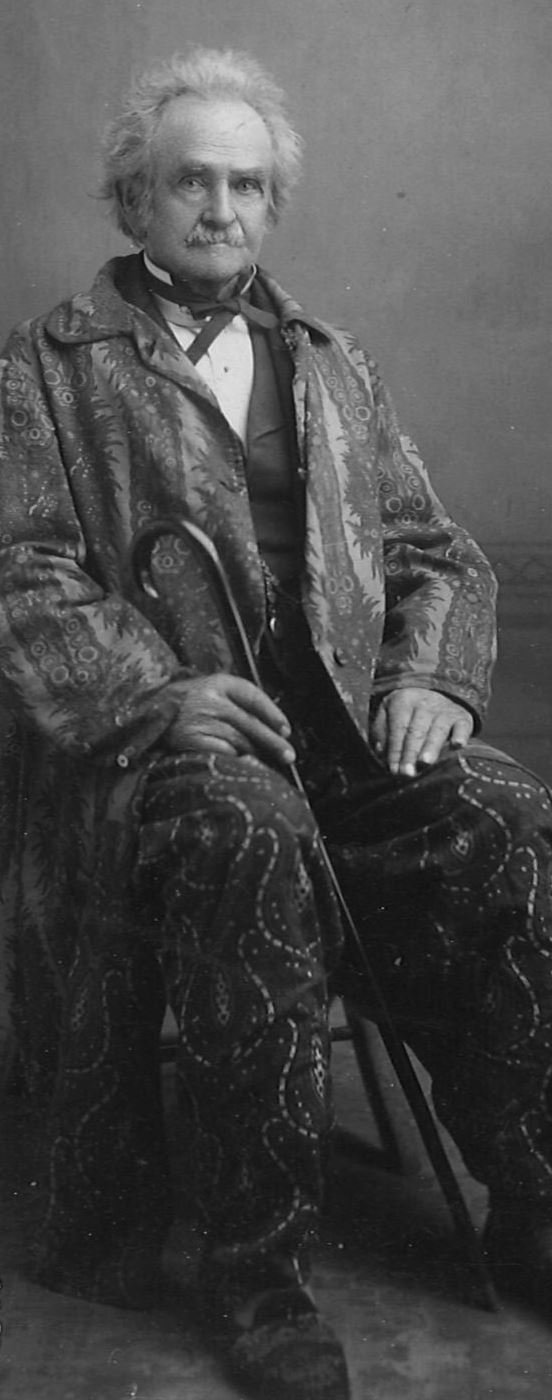

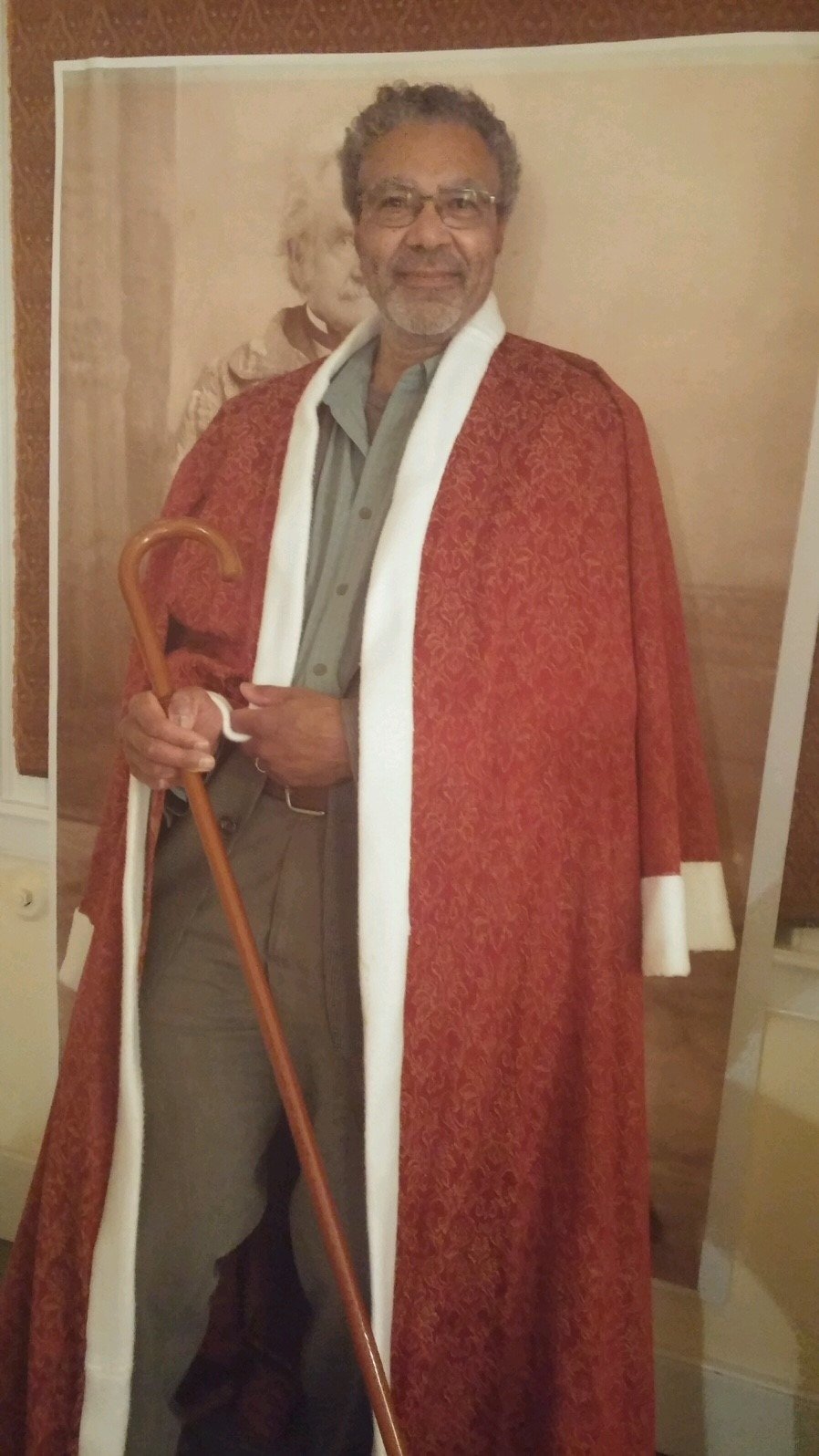

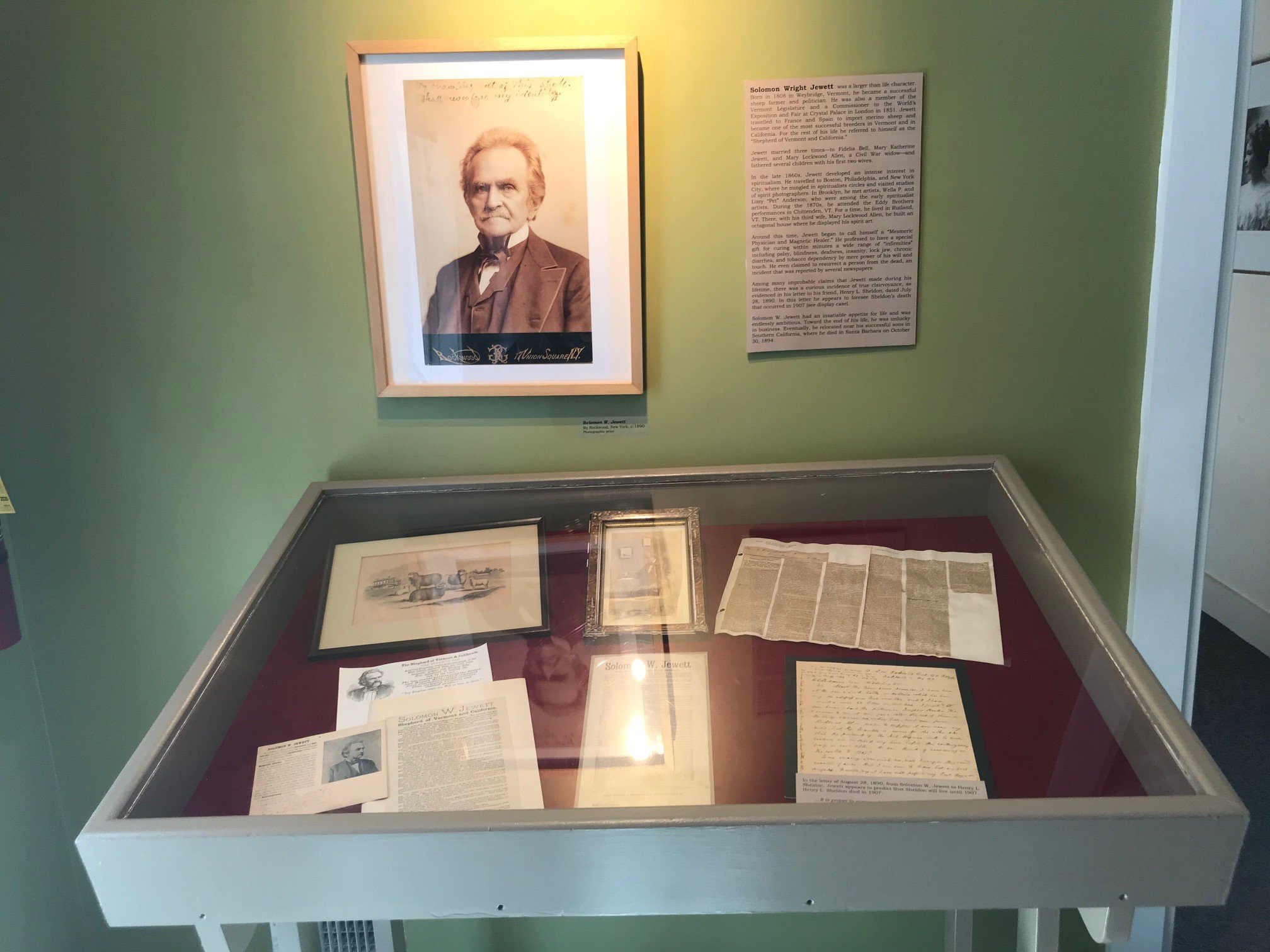

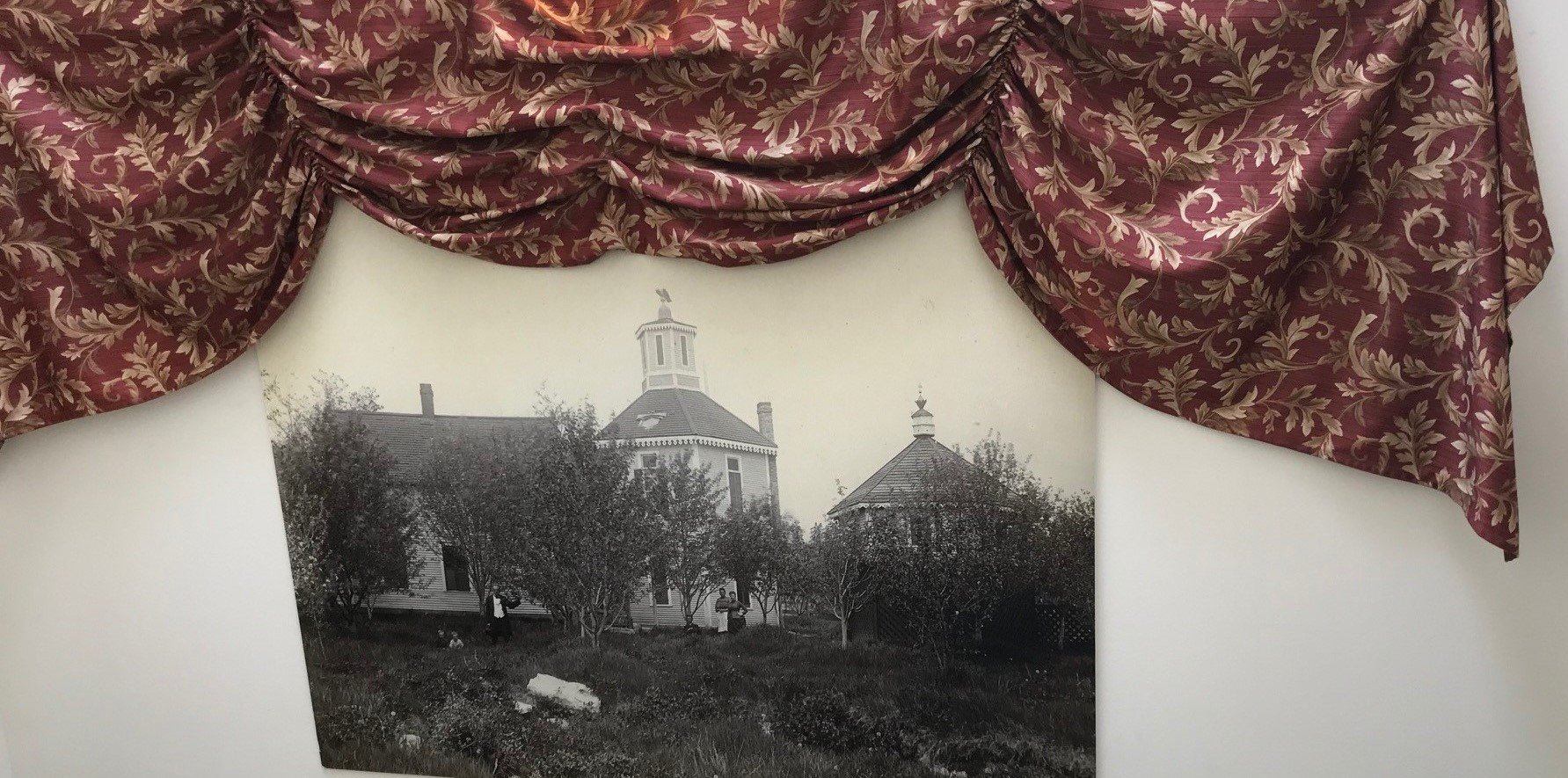

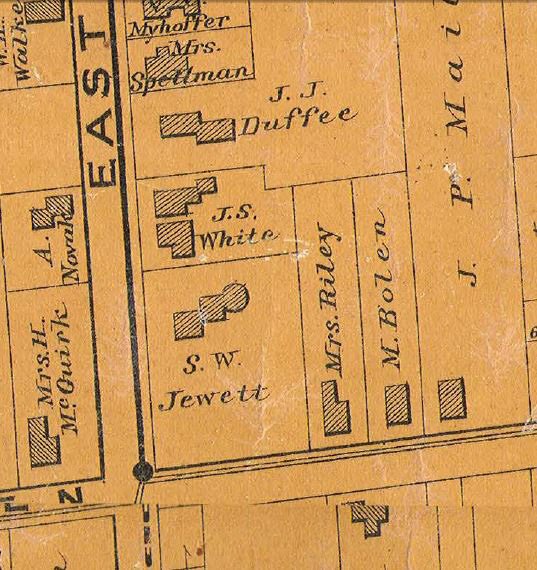

The exhibition “Conjuring the Dead: Spirit Art in the Age of Radical Reform,” on view from September 20, 2019 through January 11, 2020, presented spirit photographs and original spirit artwork from the Henry Sheldon Museum’s collections acquired by Solomon Wright Jewett (1808-94). Jewett, born and raised in Weybridge, Vermont, became a successful and wealthy merino sheep farmer and legislator in the early and mid-19th century Addison County. However, he also had great personal ambitions and far-reaching interests beyond farming. While fulfilling his goals, he led a colorful and eventful life in Vermont, Wisconsin, and throughout California. Jewett also traveled on multiple occasions across Europe (Spain, France, and England) and to New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, and other locations throughout the country chasing after his business interests and reveries.

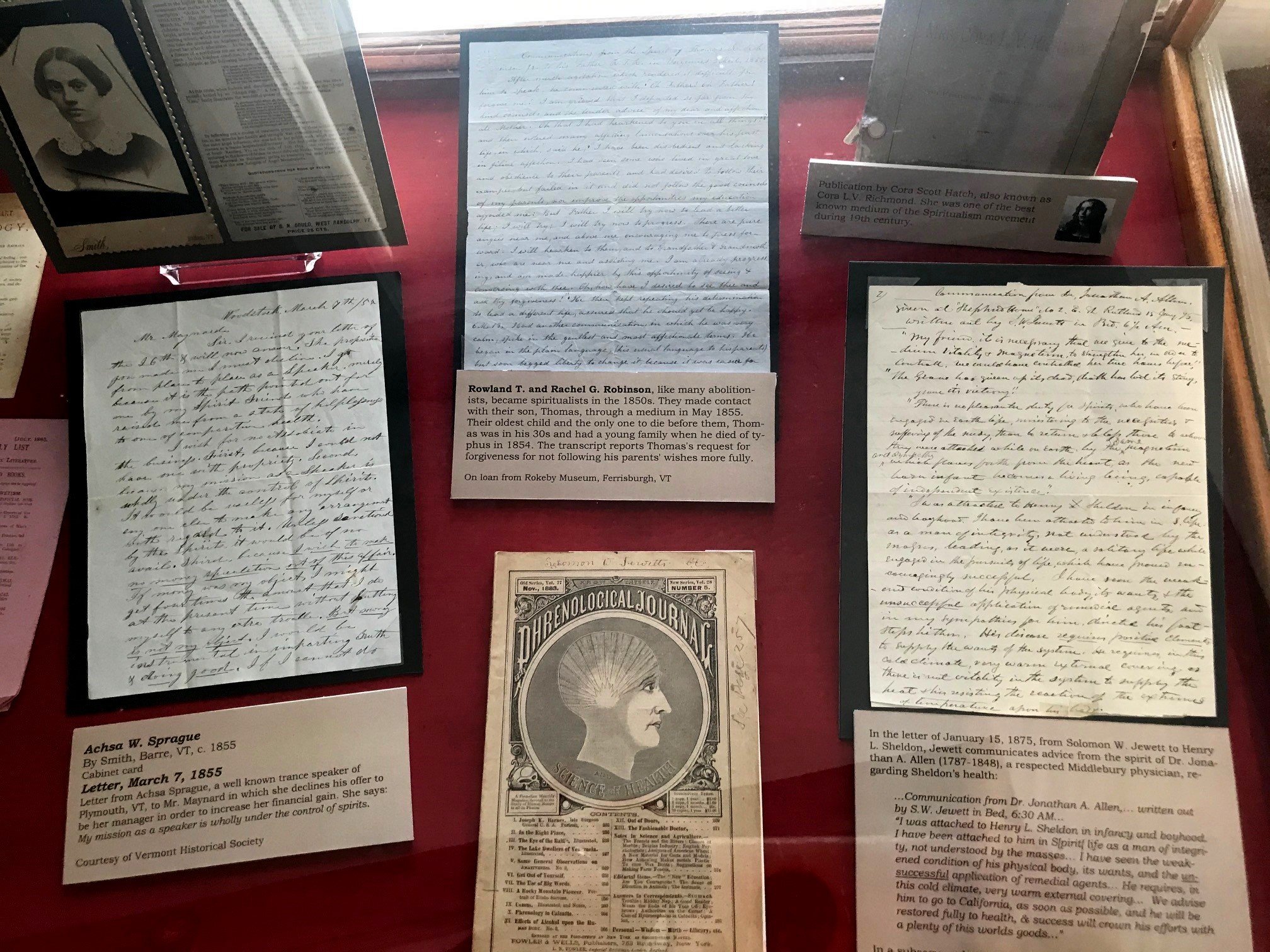

In time, Solomon Jewett began to call himself a “Shepherd of Vermont and California,” “Indian Healer,” “Doctor of Magnetism,” and “Medical Doctor.” He claimed supernatural powers in that he could cure multiple ailments and bring people back from dead. He was a strong believer in Spiritualism, a movement that preoccupied many people in the U.S. before and especially after the Civil War.

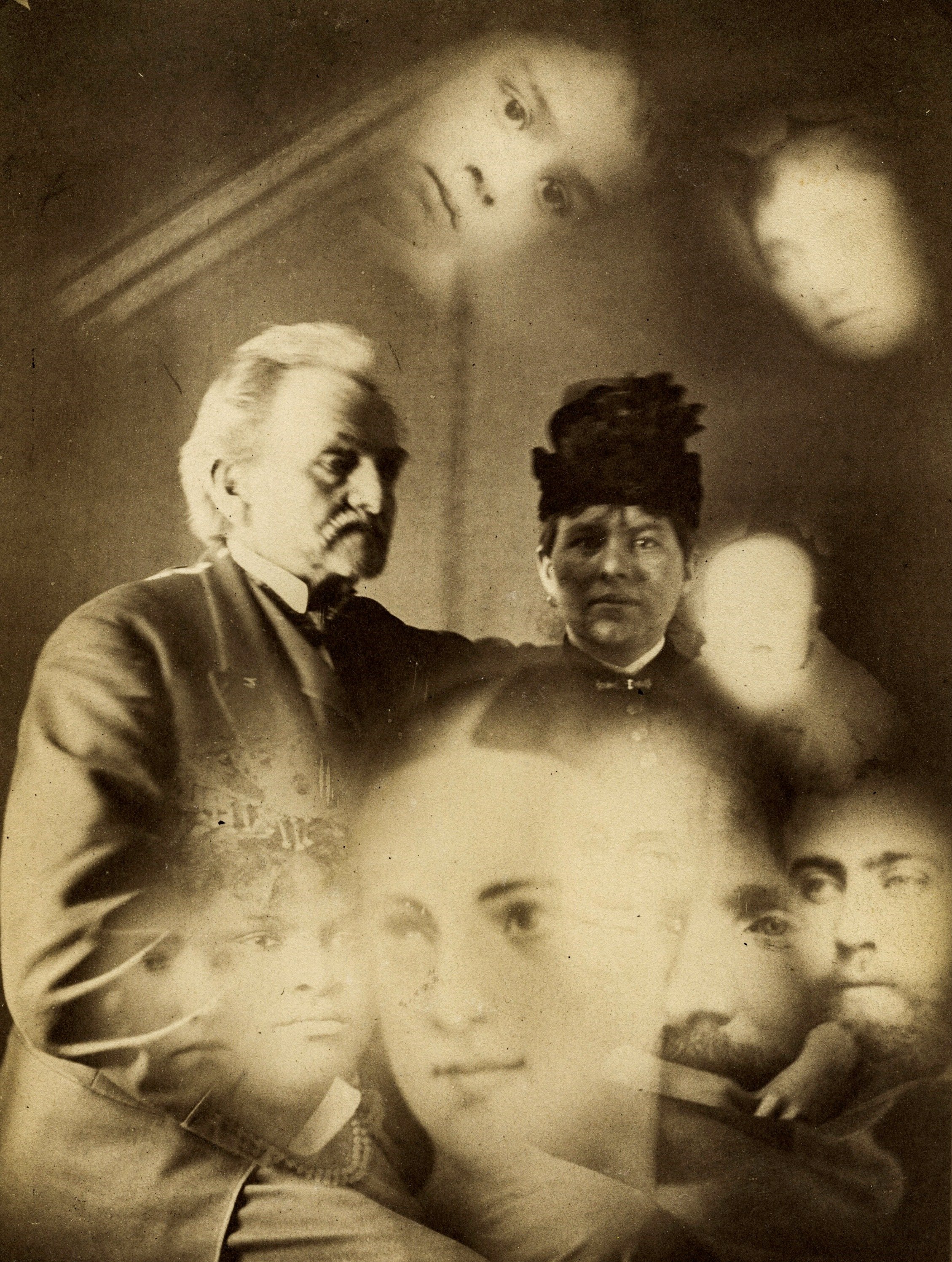

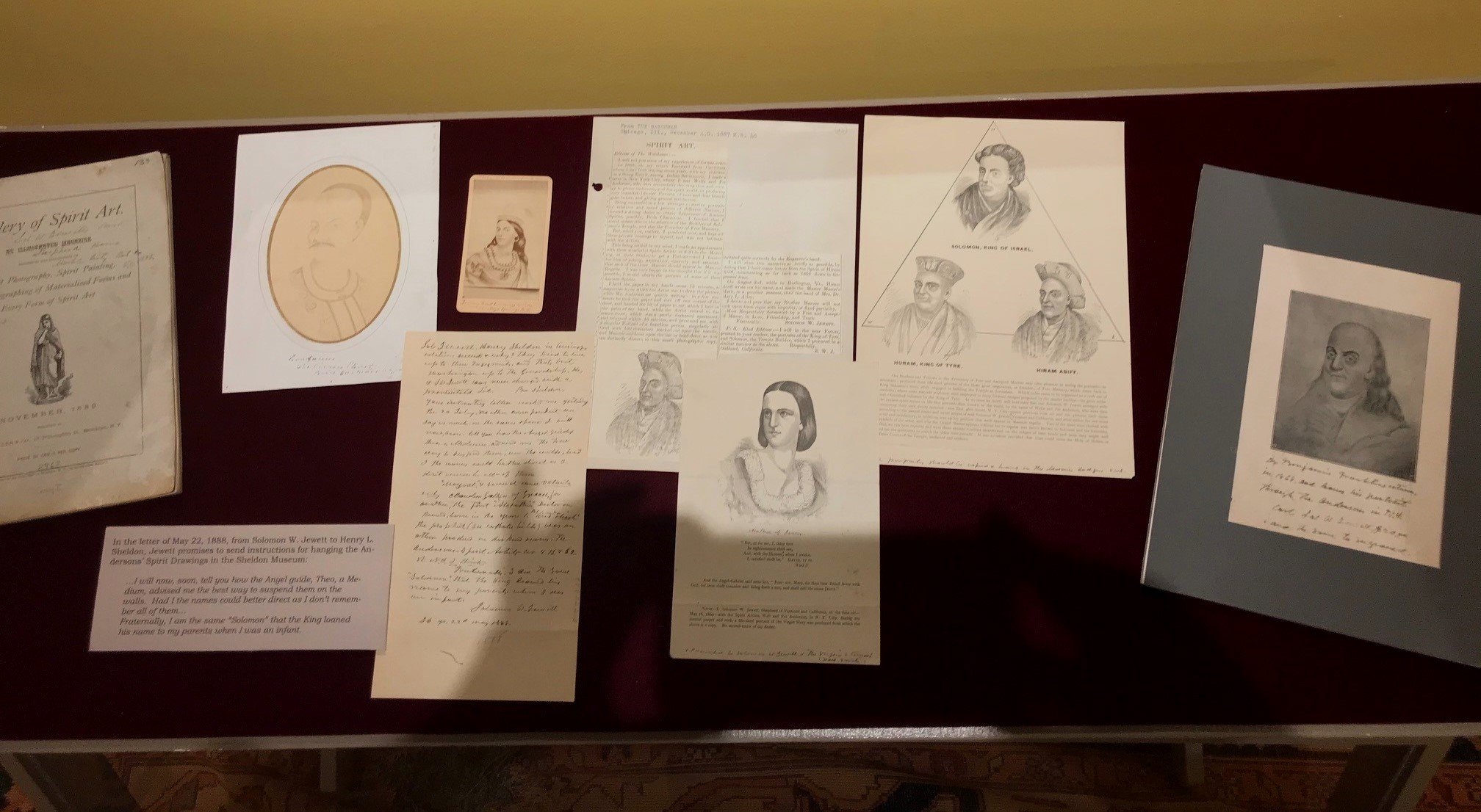

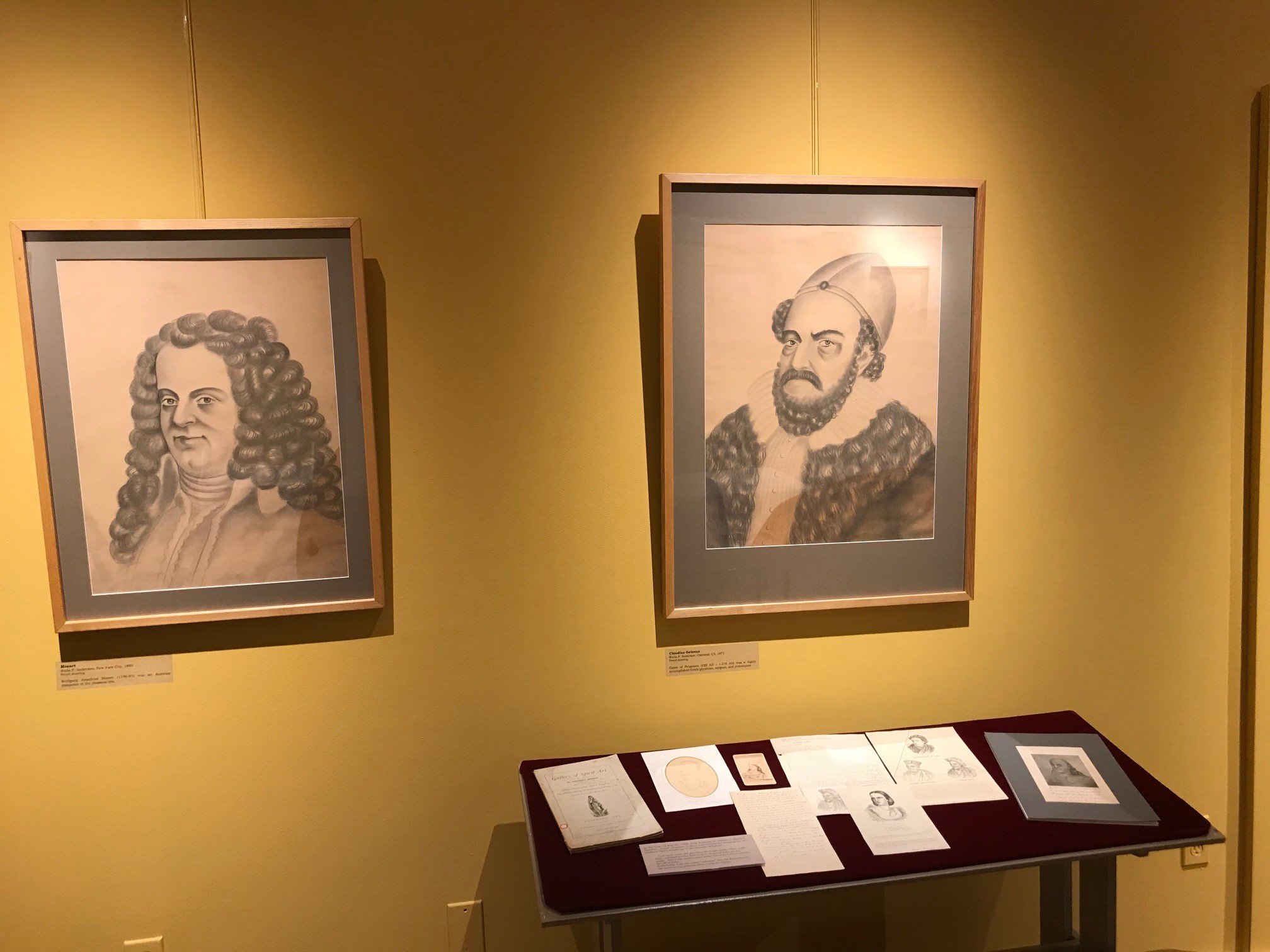

Jewett left behind a collection of “spirit photographs” and ephemera in which he appeared to be visited by notable figures, including President George Washington and Britain’s Prince Albert. He also associated with and befriended a spirit artist, Wella P. Anderson and his wife, Lizzie “Pet” Anderson, a medium, who worked in New York City and Oakland, California. Jewett acquired from them eighteen pencil portraits that depict well-known historical and mythical figures spanning many geographical locations and historical times that apparently “visited” the artist under the influence of Jewett’s presence. Anderson’s drawings are now mostly known from photographs and the original drawings in the Sheldon’s archives are rare.

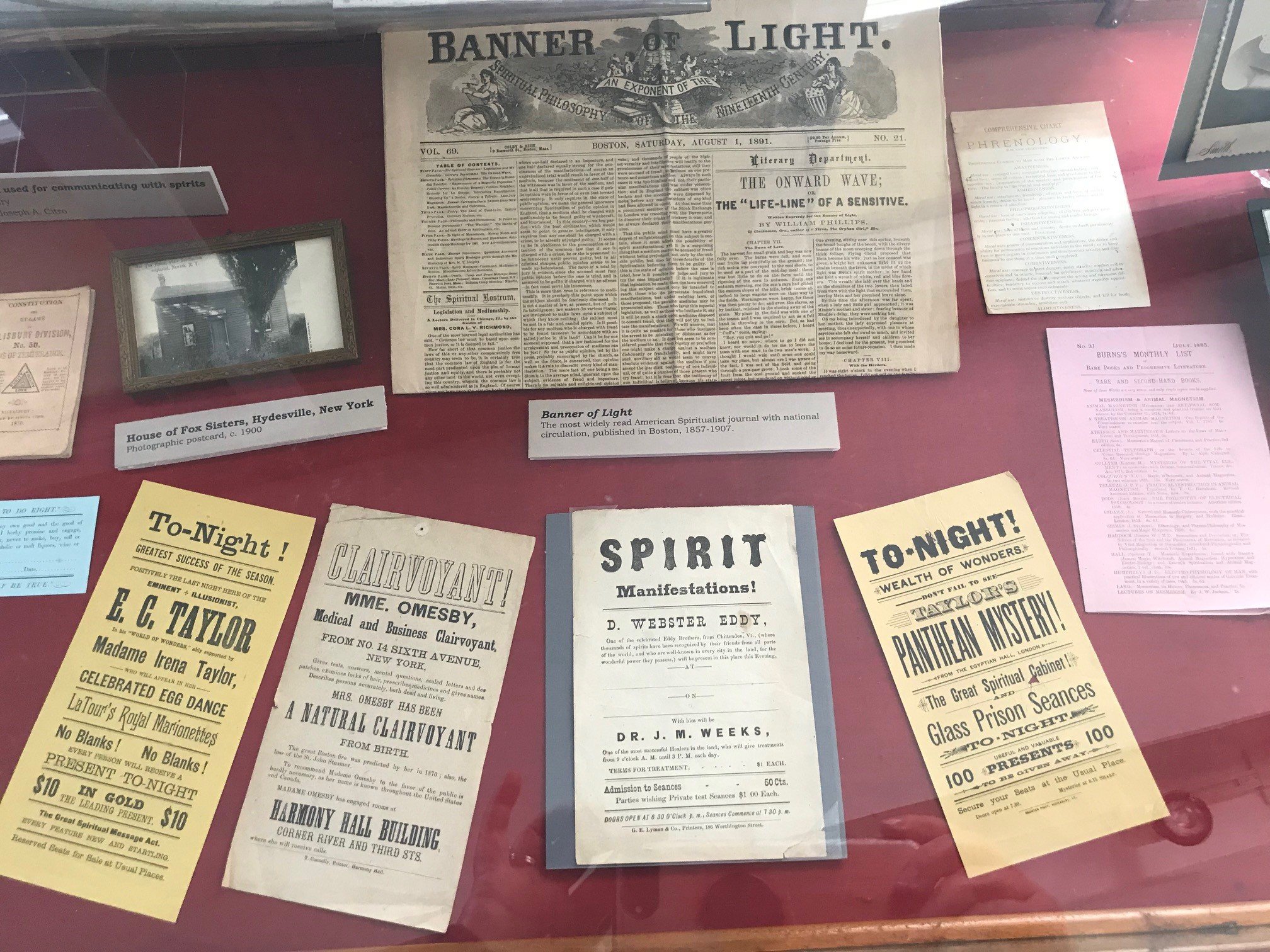

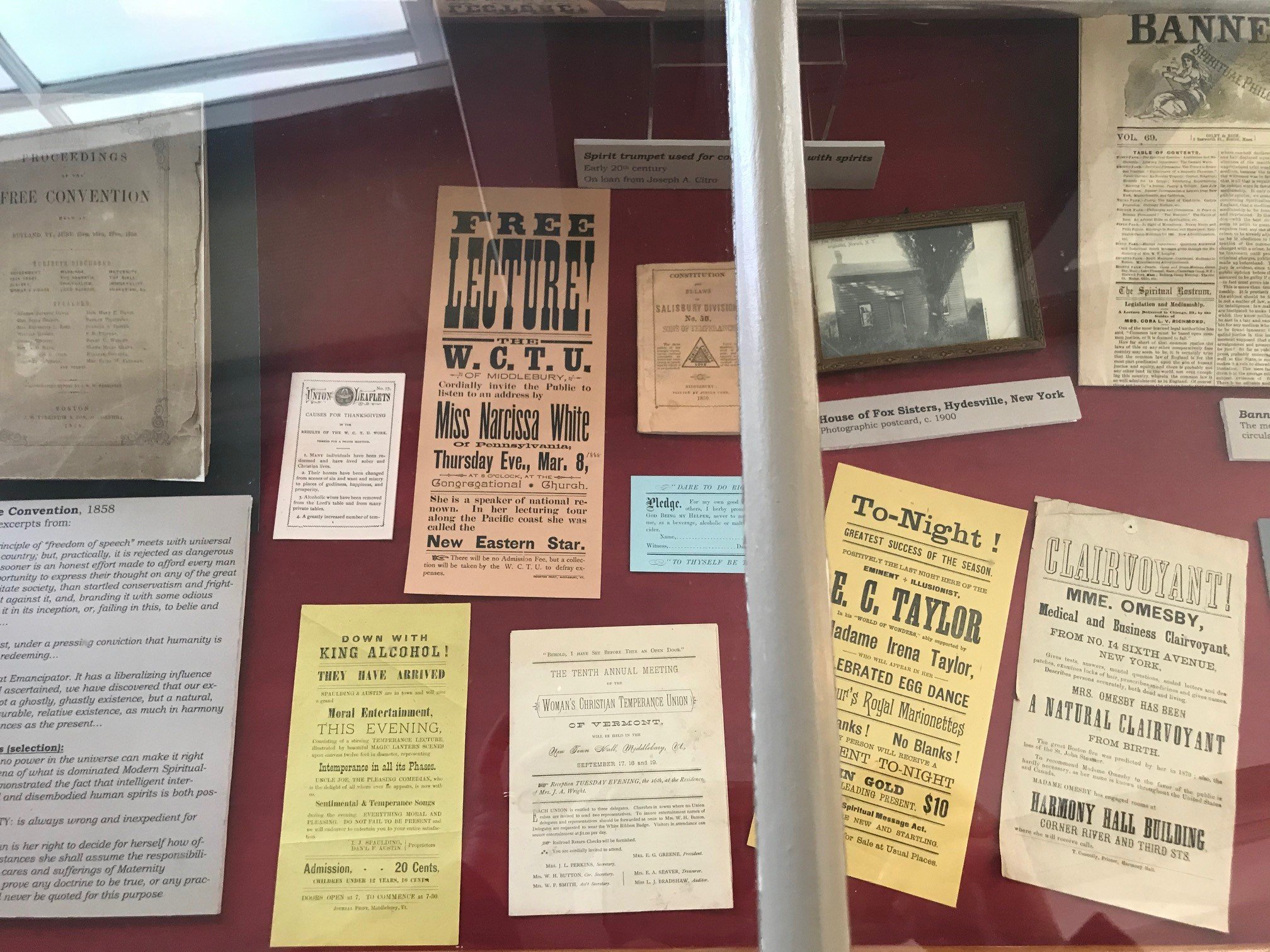

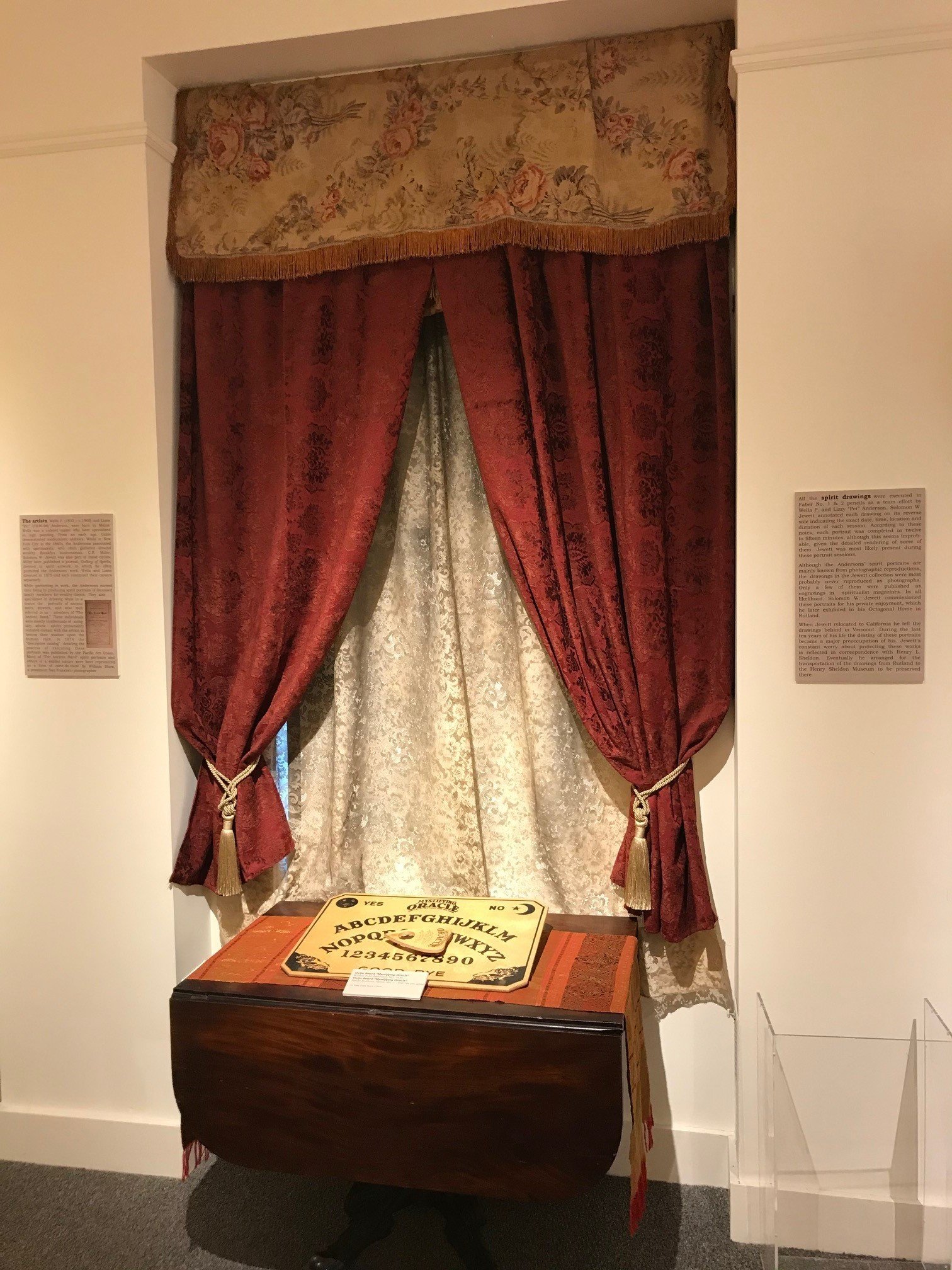

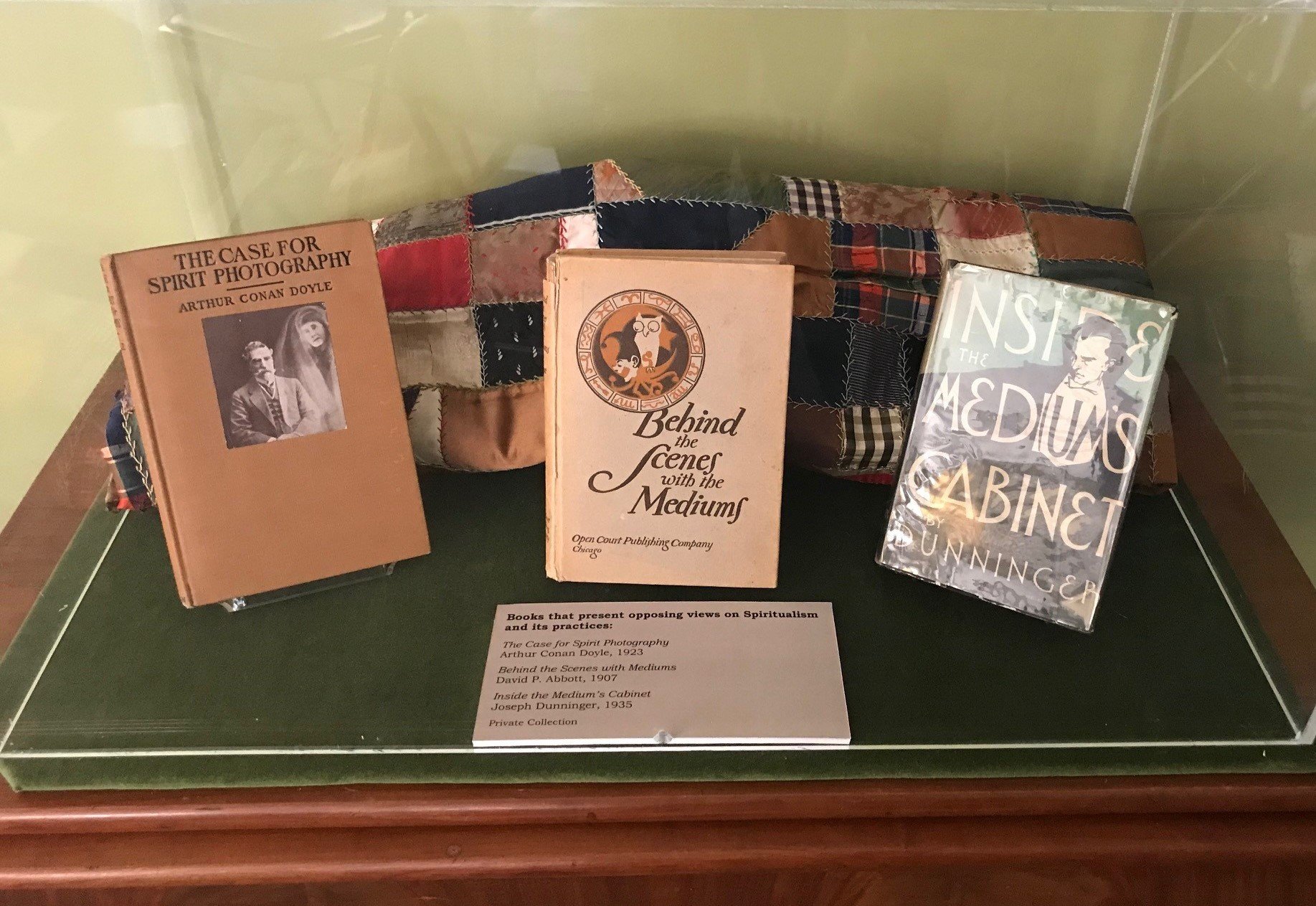

The exhibit included a colorful pastel portrait of the Indian chief, Tecumseh, by British artist James Carling (1857-87) from the Jewett collection. Carling, who spent a short time in the U.S. working as a “street artist,” is best known for his striking illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven,” now at The Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia.The exhibition was supplemented by ephemera, pamphlets, and objects that will provide a rich context to the rise of Modern Spiritualism. It stemmed from a number of radical religious and social movements, including Mormonism, Millerism, utopianism, abolitionism and women’s suffrage, many of which originated and took a strong hold in Upstate New York and Vermont beginning in the 1820s. The exhibit also featured several programs and events.

View video of Bill Hart’s 10-10-19 talk “Sinners, Prophets and Seers”

View video of Dale Cockrell’s 11-7-19 talk “The Hutchinson Family Singers: Huzzas, Horrors, and Bumps in the Night”

View video of Stephen Wehmeyer’s 11-14-19 talk “By Seen and Unseen Hands: Spirit Artists and their Art in the 21st Century”

View Images From The Exhibit Below!

(click the photos for more information)

A Note on Indigenous People in Spiritualism

Native Americans were often summoned during séances as “Indian guides” to help navigate the spirit word. Spiritualists dissented from the American governmental policy of Indian removal and the spiritualist press was a lone progressive voice in defense of rights of Native Americans.

American Indians were greatly romanticized in their depictions and often represented an earlier, more ideal period of American history. Tecumseh and King Phillip, both remembered as tragic heroes, are examples of such representations.

Locally, the Eddy Brothers, well known mediums from Chittenden, Vermont, summoned during their séances numerous full body materializations of Native Americans. One of them was Honto, most likely, an imaginary, not historical Native American woman.

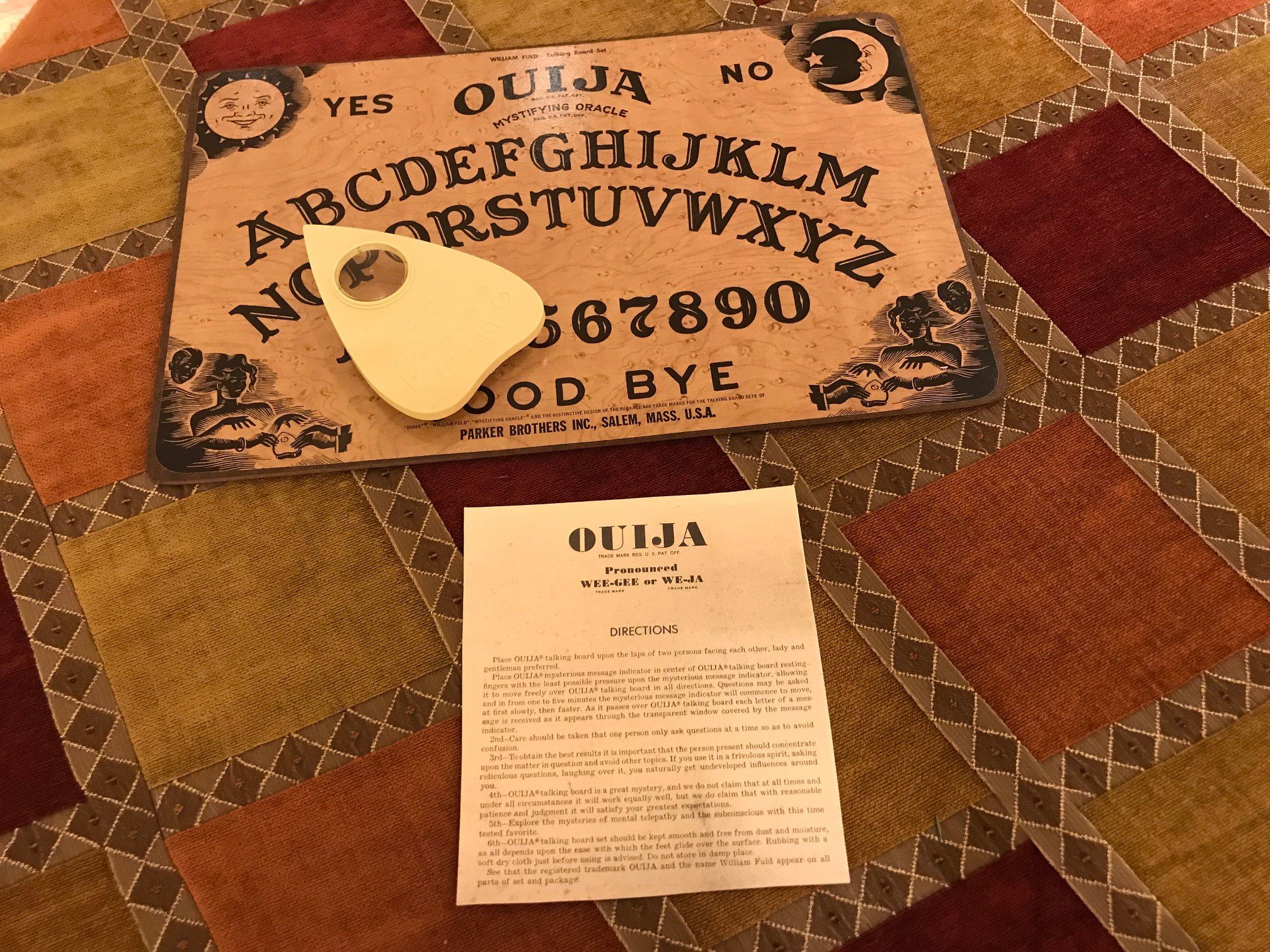

In conjunction with the “Conjuring the Dead” exhibit, the Sheldon hosted a “Night at the Museum” event for Halloween. This event included tarot card reading, a séance, a “make-your-own murder scene” dollhouse, and a storytelling event for people to discuss their supernatural and paranormal experiences.