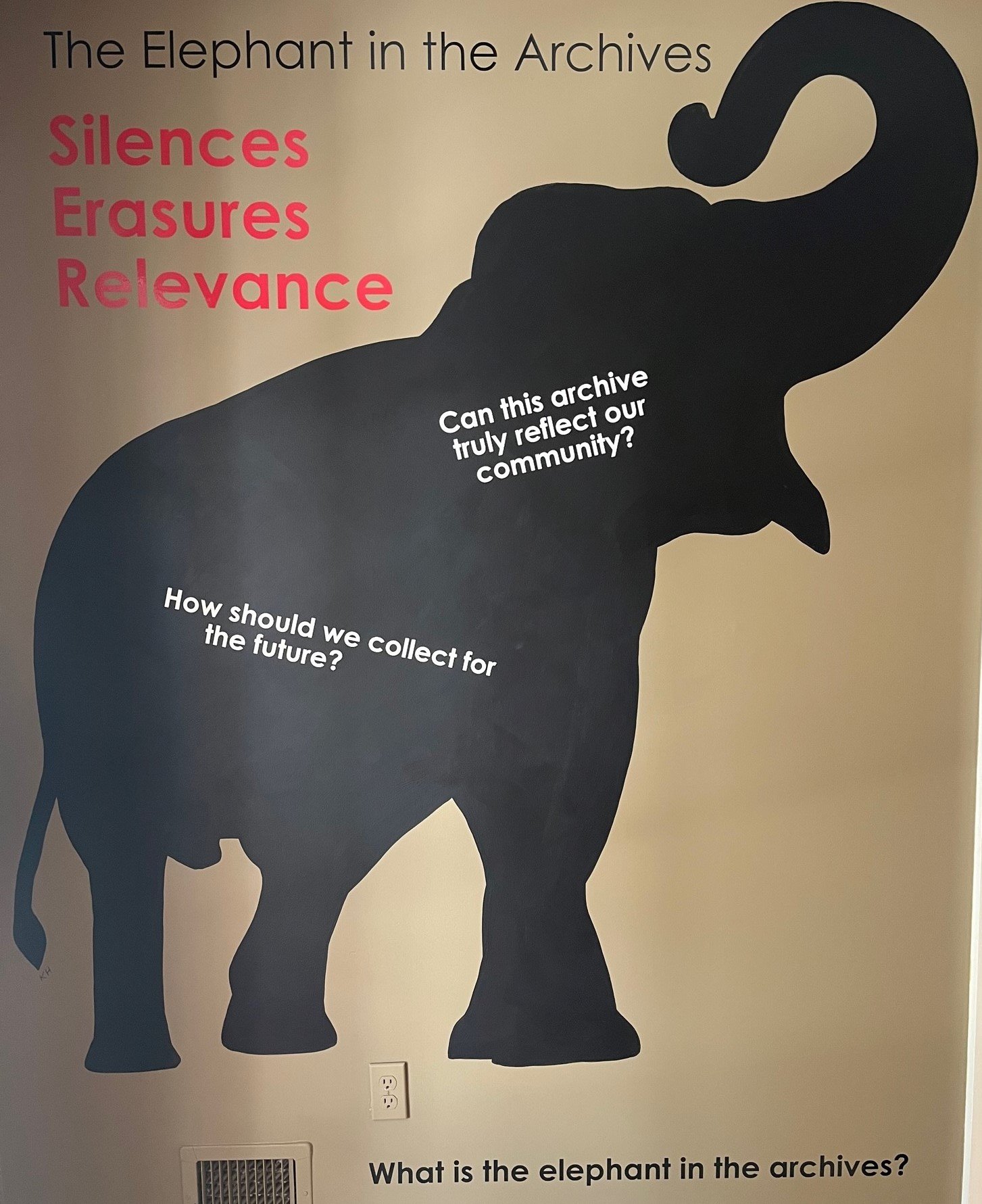

The Elephant in the archives

What is the elephant in the archives? Who is silenced, obscured, or forgotten? Can an archive be unbiased? Who decides what to preserve? How should we collect for the future? Can this archive truly reflect our community? This exhibit seeks to answer these questions and address these issues within our own archives.

Images of the Installed Exhibit

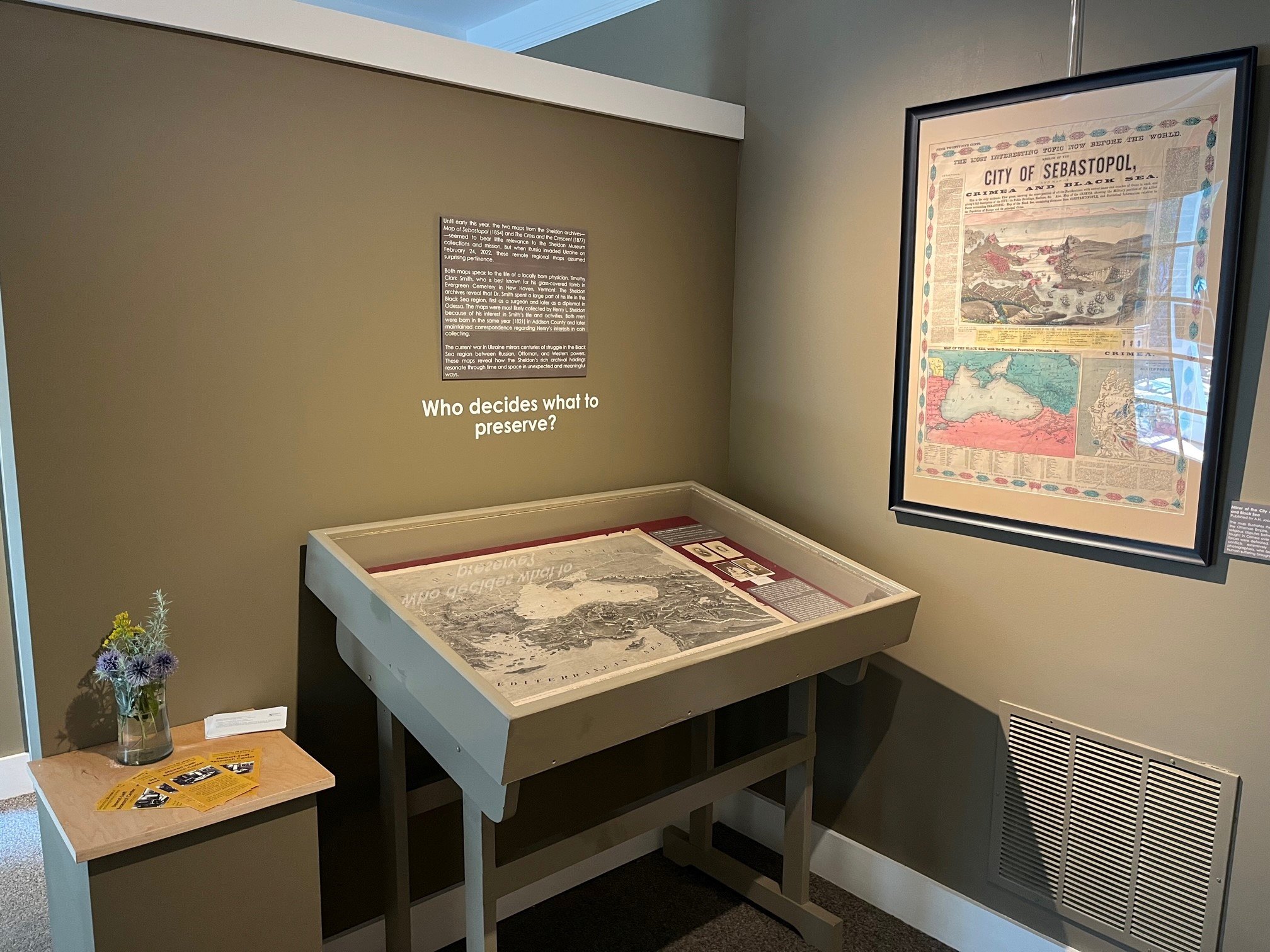

Maps and Relevance

Until early this year, the two maps from the Sheldon archives—Map of Sebastopol (1854) and The Cross and the Crescent (1877)—seemed to bear little relevance to the Sheldon Museum collections and mission. But when Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, these remote regional maps assumed surprising pertinence.

Both maps speak to the life of a locally born physician, Timothy Clark Smith, who is best known for his glass-covered tomb in Evergreen Cemetery in New Haven, Vermont. The Sheldon archives reveal that Dr. Smith spent a large part of his life in the Black Sea region, first as a surgeon and later as a diplomat in Odessa. The maps were most likely collected by Henry L. Sheldon because of his interest in Smith’s life and activities. Both men were born in the same year (1821) in Addison County and later maintained correspondence regarding Henry’s interests in coin collecting.

The current war in Ukraine mirrors centuries of struggle in the Black Sea region between Russian, Ottoman, and Western powers. These maps reveal how the Sheldon’s rich archival holdings resonate through time and space in unexpected and meaningful ways.

Timothy Clark Smith was born in Monkton, VT, in 1821. He graduated from Middlebury College in 1842 and studied medicine at the University of the City of New York, graduating in 1855. In 1856, he enlisted as a staff surgeon for the Russian Army. Later he served as US Consul in Odessa from 1861 to 1875, and in a similar capacity in Galatz, Romania, from 1878 to 1883. Timothy Clark Smith died in the Logan Hotel, right next door to the Sheldon Museum in 1893.

In 1856, Clark Smith married Catherine Jane Prout, native of Odessa, who was the daughter of a British doctor, who served as Chief of the Port of Odessa, and Mary Liprandi of Genoa, Italy. Smith and Prout had several children, some born in Vermont and others in Odessa, who became doctors, artists, and diplomats. After completing his diplomatic appointments, Smith returned to Vermont. Later in life, he suffered from taphophobia—the fear of being buried alive—and designed his own grave topped with a horizontal glass window and stairs beneath. His tomb in the Evergreen Cemetery in New Haven, VT, remains a popular tourist destination. But Timothy Clark Smith offers stories beyond than his curious grave and more awaits to be revealed about his life in the Black Sea region.

Mirror of the City of Sebastopol and Map of Crimea and Black Sea; Published by A.H. Jocelyn, New York, 1854

The map illustrates the military conflict between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, France, and Britain that erupted over religious disputes between 1853 and 1856. Key battles were fought in Crimea over the port of Sevastopol where Russian forces were defeated. The Crimean War was one of the first conflicts extensively documented by journalists and photographers, who brought to public attention large-scale human suffering brought on by wars.

Left: The Cross and the Crescent – Harper’s Pictorial Map of the Seat of the War of the East

Supplement to Harper’s Weekly, 1877

War has been almost constant in the Black Sea region since the 16th century. This map conveys the political situation during the last of the Russo-Turkish wars (1877-78).

Right: Smith Family photographic portraits (cartes-de-visite)

All taken in Odessa, Russia. L-R:

Timothy Clark Smith, by Russkaya Fotografia, c. 1856

Catherine (Kitty Prout) Smith, by Russkaya Fotografia, c. 1856

Hermione and Alfred Willoughby Smith, by J.A. Antonopulo, c. 1872

Felix Willoughby Smith, by J.A. Antonopulo, c. 1872

Maps and Erasure

Nova Belgica et Anglia Nova

Published by Johannes Janssonius, Amsterdam, c. 1647

Janssonius’ map presents New England to white Europeans as a land of opportunity, not a place that is inhabited by Native peoples. The map highlights the land’s economic potential, rich in furs, pelts, lumber, and other natural resources, an important point to convey to a Dutch Republic on the brink of a new imperial project westward. The map obscures the presence of Indigenous people in North America, who are alluded to in the depiction of a settlement in the map’s upper left corner. The map’s only other nod to Indigenous presence resides in the titular cartouche, which is flanked by a pair of “Native” figures whose unclothed bodies are largely ornamental.

Maps of New Hampshire &Vermont

(Left) Plan of Johnson, VT

Manuscript survey by Eben W. Judd, c. 1788

Eben Judd’s early survey of Johnson, VT, shows a grid of neatly partitioned land with only European settlers’ names, demonstrating how land partitioning and surveys codified settlers’ legal rights to appropriated land.

(Right) New Hampshire & Vermont

Published by S. Augustus Mitchell, Philadelphia, 1846

An 1846 map of Vermont and New Hampshire includes population statistics showing a sharp increase in European settlers between 1701 and 1790. By the time this map was created in the mid-19th century, Native peoples have been marginalized to the names of natural features, such as Winnipiseogee Lake or the Souhegan River, with no indication of existing Indigenous communities.

Indigenous Peoples

(Top Left) Sketchbook of Cyrus B. Stow (1833-1904), 1881

An 1881 sketchbook kept by Cyrus B. Stow (1833-1904) includes drawings of Native American tools, many found in the Middlebury area. The author offers a warning to potential thieves: “Notice. Steal not this book for if you do I will take a tomyhawk and then scalp you.” A 1940 talk by Harry M. Woodcock from our archival collection invokes similar stereotypes about the ferocity and “savagery” of Native peoples.

(Top Right) Early Indians in the Champlain Valley

Excerpt from a talk delivered at the Sheldon Reunion held in Middlebury in 1940, the typescript of which is housed in the Sheldon archive:

“The Iriquois were an active, aggressive, and warlike race; they were perhaps more often victorious than otherwise. Their war parties ranged the eastern woodlands, from the River St. Lawrence far into the deep south; from the rivers of Maine to the Mississippi… During this long age of warfare this region became a regular no-mans-land, and such it continued to be until the white man came. The pre-historic period ended when that Knight of France, Samuel de Champlain, fire his musket at the Iroquios chieftain at Crown Point a July day in 1609.”

(Bottom) Arrowheads)

Arrowheads and other stone implements excavated in Addison County farmlands provide archaeological evidence of early Native presence in this region. The Sheldon houses several collections related to Indigenous culture, but little study has been undertaken to better understand these artifacts in our Museum. Without their cultural context, these artifacts read as relics of extinct race, not dissimilar to dinosaur fossils, rather than historical tools of a distinct, rich, and ongoing culture.

Indigenous Stereotypes

The Sheldon’s 19th-century ephemera collection includes many advertisements that present Native people in a stereotypical and largely romanticized fashion as picturesque “Indians.” In many cases, this recycled Indigenous figure lends the veneer of ancient wisdom to white-produced medical tonics and miracle cures to increase profit. A broadside advertising the opportunity to view a “real Western Indian” points to a genre of well-attended local performances predicated on the commoditization of Indigenous peoples. A storage tin produced by S.A. Ilsley & Co. depicts Columbus’ arrival on American soil, where he is greeted by a kneeling Native figure, whose reverent and subservient pose attests to European right to the land.

Women and Silence

Unknown Women

This installation pairs an array of anonymous women from the Sheldon archives with a bust of Philip Battell Stewart (1865-1957) in order to reflect on the weight that prominent men receive in our collection. Stewart was Vermont royalty, the son of John Wolcott Stewart, the 33rd Governor of Vermont and brother of Jessica Stewart Swift, whose benevolence underwrote the creation of the Stewart-Swift Research Center. This bust attests to the monumental presence of men of privilege in museum collections.

Our collection includes endless images of unnamed women spanning from the early 19th century to recent decades. Although the Sheldon archives hold materials pertaining to women’s history, our collections disproportionately focus on male lives and achievements. Images like those presented here offer glimpses into the rich and varied experience of the women whose lives are not otherwise recorded in our collections. For every Philip Battell Stewart whose name and likeness are etched in marble, there are dozens of anonymous women whose identities and experiences have been lost to history.

As you will notice, the women of this archive are markedly white and middle class. With few exceptions, Sheldon collections offer little evidence of people of color, queer people, service workers, or countless other communities whose histories and experiences have been silenced in the historical record.